Usual and Unusual Cold in Early Allamakee County

Allamakee County, Iowa

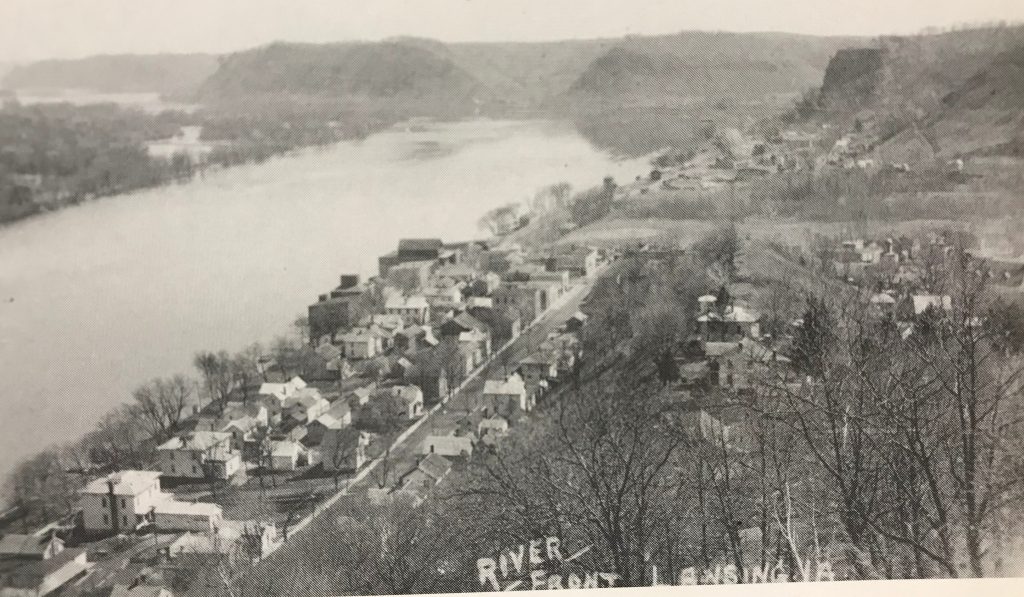

When Thomas Corwin Medary writes of his first months as a young printer and journalist in Allamakee County, he recalls himself and two fellow journalists approaching the expected winter cold with high spirits. In 1859, having lost jobs at the Waukon Journal due apparently to the drinking habits of its owner, publisher, and editor, the three young men first wrote and sold their own printed poems to raise the stage fare, then traveled to McGregor looking for work. That didn’t pan out, but they did find jobs at The Lansing Mirror. Apparently the men were staying across the river from McGregor, for Medary writes, “The next morning we set out for McGregor bright and early, again walking across the river on the ice, and reaching McGregor in time to take the morning stage for Decorah on our way to Lansing, our object in going by Decorah being to see if we could not get some of our ‘back salary’ but in which we did not succeed….We shall never forget our Midwinter’s ride from McGregor to Decorah. Our seat was on the outside with driver [Tom] Tokes [a man of partial Native American descent], the inside of the coach being filled with other passengers, and as we were without an overcoat, and perhaps no under-clothing, and as the weather was intensely cold, we suffered terribly from the piercing blasts of one of Iowa’s old-fashioned winters.”

Once employed at the Mirror in Lansing, the “boys had to skirmish around to get” the wood to heat their workroom as “the office was often without wood.” “Skirmish” in this case means steal from woodpiles around town. Medary confesses that they felt a little guilty when someone came into the office and “remarked that he recognized his wood piled up by the stove!”

If Medary’s recollection of NE Iowa’s usual 19 th – century winter was cause for comedy, the 1940 Armistice Day blizzard was an unusual storm that resulted in tragedy—in Allamakee County and throughout much of the country. It was a monster of a storm that formed in Washington state where it took out a major bridge in Tacoma. But weather communications were such that folks in places like Allamakee County enjoying a November 11 holiday in 50+ degree weather were not forewarned. It seemed to be the perfect day for duck hunting along the river, especially as large flocks of water fowl were sighted in the area. “Across the Midwest, hundreds of duck hunters, not dressed for the cold, were overtaken by the storm. Winds came suddenly, then masses of ducks arrived flying low to the ground. Hunters, awed by unending flocks of birds, failed to recognize the impending weather signs that a change was in process.” As temperatures fell rapidly, rain changed to sleet then snow and visibility diminished to zero making it impossible for hunters to return to shore. 70-80 mph winds and 15-foot swells intensified the danger; hundreds lost boats and gear and some lost their lives by drowning or freezing as temperatures dropped to single digits.

This seminal weather event has lived so long in human memory because extreme weather and human practices together resulted in frightening conditions and loss of life. The Armistice Day holiday from work freed many to pursue the common November practice of duck hunting inspired, in this case, first by warm temperatures and then by large numbers of birds driven to low altitudes and across the Midwest by powerful winds.

Sources: SHSI: “Journalistic Adventures and Personal Reminiscences of Thos. Corwin Medary,” in April 1943 journal of his son; “Armistice Day Blizzard of 1940 Remembered,” National Weather Service, web.