Tornado Tears Down Maple Grove and A Bit of Madison County History

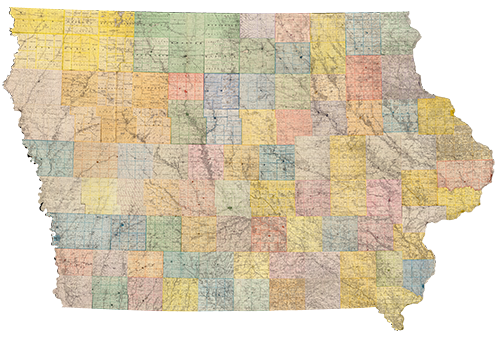

Madison county, Iowa

Beck O’Brien

1911

A grove of maple trees especially precious for their sap was ruined by the cyclone that wreaked havoc on the eastern half of Madison county one day in the fall of 1911. The storm carved a path from Tileville to Wick, destroying farms, homes, and barns along the way. But it was Mrs. Selby’s farm, with its grove of maple trees, that is reported to have suffered the most damage. “In the fine sugar tree grove,” after the storm, “there was hardly a whole tree left.” Her barn and “other buildings” were also damaged, “[lying] in a mass of ruins, mixed up with broken sugar trees.”

The loss of maple trees in Madison County must have been particularly devastating because of this part of Iowa’s rich history of maple sugaring. It is a tradition that historians have traced back to the Meskwaki who lived in what would become Madison County prior to the settlers. Even after the Meskwaki were forced to leave their homelands and move to Kansas in 1845, they continued to visit the area to tap the maple trees.

Maple sugar was very important to the Meskwaki, and they would not trade nor sell their maple sugar to settlers. It was a product specifically used for “inter-tribal barter, ceremonial or personal use.” According to Meskwaki Tribe member George Young Bear, the Meskwaki had “a custom of using maple sugar in their own families, as well as [for] exchange with neighboring tribes.”

When the Meskwaki produced maple sugar, they would “relocate to ‘sugar camps’ near the soft maple trees along the river bottom.” There, they would build a large wickiup, inside which they would boil the sap in pots that hung over the fire. To get the sap to the wickiup, someone would carry buckets on a wooden yoke, two at a time. Other family members would tend to the fires beneath the pots, making sure they did not die out. The same people would be in charge of tending to the boiling buckets of sap.

“The pair boiled the sap into syrup and brown sugar, stirring the pots for hours in the sweltering dome, which had been piled with rush mats and potato sacks to trap heat. This process could produce 100 pounds of maple sugar in a single season, which tribal members used during ceremonies and as a condiment.”

After forcing the Meskwaki out of the area, the settlers decided they too wanted to harvest the sap to satisfy their sweet tooth. After all, cane sugar was in low supply and high demand, making it “an expensive luxury.”

Both the settlers and the natives recognized the effect of weather on the sugaring season. Natives knew that the cold would harm the flow of the sap, and a cold snap during the warmer months could bring production to a halt. Settlers also noticed that the sugaring season only occurs when the sap thaws in the daytime and freezes at night. So, the season could begin as early as January or as late as April. Either way, once the weather became consistently warmer, usually May, sugaring would no longer be possible.

The settlers’ process of making syrup and sugar was a little different than that of the Meskwaki. Early on, the settlers pushed the task of carrying the sap onto oxen, who would pull a sled with a whole barrel of sap. The sap would be boiled in iron kettles and then strained through cloth to get rid of impurities. Next, milk, eggs, or both were added to the sap, which was boiled. This process brought even more impurities to the top of the kettle, which were skimmed off. Boiled a little longer, this sap transformed into syrup. One county historian wrote of the treat: “Nothing was better to be eaten with corn bread, Johnny cake, or buckwheat cakes, than good maple syrup.”

However, many of the settlers were looking for a substitute for sugar. In that case, the syrup needed to be processed further. For hard sugar, the syrup would continue boiling until it could solidify in cold water. This type of sugar was formed into molds. Maple sugar as a substitute for cane sugar was made by continuing to stir and boil the syrup until it formed a crumbly consistency.

One historian reminisced about the ‘sugaring off’s” of his childhood. This was an event in which children visited the sugar house at night during the last part of the process and were given maple sugar to eat.

“Those splendid maple sugar groves are about all gone and the pleasant memories will soon go with them, for in a few years there will be very few living that ever helped make sugar in Madison County. The places of those groves have now become our richest cornfields, from whose products we get the glucose syrup, usually set upon our tables, presumably to look at, for very few eat it. Would that we could go back to those early days, help bring in the sap, sit around the kettles and feed the flames that would boil down the sugar water into delicious syrup or sweet tasting sugar!”