Prairie Chicken Dinner, Sac County

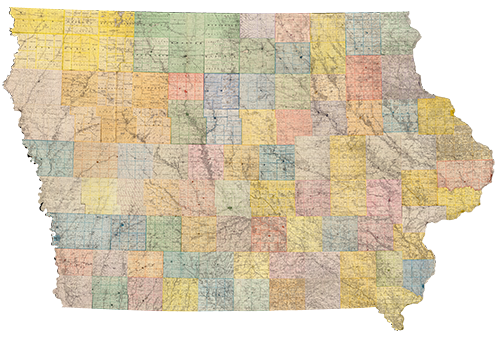

Sac county, Iowa

Beck O’Brien

The pinnated grouse—commonly known as the greater prairie chicken—was once well-known among Iowa’s settlers, who revered it for both its taste for grasshoppers and its tasty meat. In Sac County, the grasshopper brigade led by Washington Allen took prairie chickens’ well-being into account when deciding when to permit property burns.

When the Sac County grasshopper brigade first met in September 1876, they assigned themselves the duty to “not kill prairie chickens, or any other kind of birds that eat grasshoppers, and that we forbid all parties from killing on our premises.”

This certainly would have been a difficult proposal to enforce among the people of Sac County, considering prairie chickens were hunted and trapped extensively in the Midwest during the European settlement period. Greg Hoch, author of the book Booming from the Mists of Nowhere, wrote:

“Some have argued that the prairie-chicken, perhaps along with deer, was a key species in the diet and economic life of many settlers. Many pioneer families might have starved during the winter without prairie-chicken dinners. Sending prairie-chickens to eastern markets probably kept a few farms and farmers solvent during hard times. Prairie-chicken hunting drew many eastern hunters to the Midwest.”

However, the brigade clearly recognized the importance of preserving the prairie chickens, if only to help destroy the grasshoppers. One of the challenges with delaying a burn is that the grasshoppers might hatch early and begin to feast on the fields. Some settlers wanted to burn the fields prior to the hatch, but that would kill both the grasshoppers and the chickens. If the burn does not kill all the grasshoppers, and there are no chickens to eat the grasshoppers who do hatch, there would still be a grasshopper problem.

Another factor to be considered is that primarily young prairie chickens eat grasshoppers. So, even if adult prairie chickens were spared but their nests were burned, there would not be as many insects eaten by the mature chickens as there would have been if the chicks had hatched. Within the first few weeks of a prairie chicken’s life, her diet is almost entirely made up of insects. When she hatches she weighs 0.03 pounds, and by the fall she weighs two pounds. Later in life, she will eat mostly fruits and grains.

Prairie chickens were once plentiful in the plains. In 1910, one ten or eleven-year-old boy was helping his uncle move from Fertile, Minnesota to Hillsboro, North Dakota in a horse drawn wagon. At meal-time, the boy would “go out in front of the horses with a stick and knock down enough “chickens” to cook up for that meal.”

In Illinois, one estimate places the number of prairie chickens in the state in the mid-1800s at fourteen million. In the mid-1960s and early 1970s, the population expanded from 40 to 206 males on 660 acres. In 1994, however, there were only 6 males on the same habitat, likely because of population isolation. Overall, the prairie chicken has disappeared from ninety percent of the land it once populated.

The greater prairie chicken is faring better than some of its cousins. The heath hen went extinct in 1932. The prairie hen, which lives in southeast Texas is on the endangered species list in the U.S. The greater prairie chicken is thriving well enough that it is still available to legally hunt in Colorado, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

Some of the greater prairie chicken’s population decline can be attributed to hunting, predators and parasites. However, several other factors have affected the species, including a lack of fire. In 1980, one researcher wrote: “Smokey the Bear has perhaps been the worst enemy of the prairie chicken.” This is because fires are needed to maintain grasslands for the chickens to live in.

The replacement of natural prairie habitats in the Midwest with farms and woodlands is one of the main reasons the chickens are not as plentiful as they once were. While done with good intentions, the introduction of trees to the prairie means the removal of the grasslands the chickens thrive in. So while some generalist bird species such as blue jays and chickadees have benefitted from the new timbers, some native bird populations have withered.

Other human inventions such as pesticides, wires, fences, and wind turbines have also hurt prairie chicken populations. All of these inventions go back to changing the landscape of the plains. For example, Hoch argues that it is not the propellers of wind turbines that cause the most prairie chicken deaths, but rather the infrastructure built around wind farms. In order for the prairie chicken to thrive, he needs prairie to live in. The introduction of more natural prairie land could lead to an increase in the chicken that once fueled the settlement of the Midwest, including Sac County.