In the Bleak Midwinter

O'brien county, Iowa

Even before O’Brien was officially its own county and weather records in the area were maintained, the winter of 1856-57 was one for the history books. The blizzard conditions threatened the lives of new settlers like Hannibal House Waterman, his family, a Dutch farm worker, and the lives of “Sioux” sojourners headed south from Minnesota for winter hunting—”Sioux” being the French-derived name used by whites for the Dakota-speaking peoples of the upper Midwest.

The Iowa State University weather glossary defines a blizzard as winds or repeated gusts at 35 mph or greater, sustained over at least a three hour period, accompanied by blowing snow often producing low visibility for travelers. But historians of O’Brien County found, in the origins of the word, not just natural conditions but a human social element. They remark that what would be just another snow storm in a settled county is a blizzard “in a new county. On an unprotected prairie, a blizzard, for those who are out in it, means a terrible hardship, and too often death.” That was the case in the winter of 1856-57.

Provisions being scarce in the newly settled territory and hard to acquire in the cold and snowy winter, Waterman sent his Dutch farm worker south with two yoke of oxen to acquire food. Historians report that on the worker’s way back north, the flour he had acquired was either given away or stolen by people equally desperate. And then the winter marooned the Dutch worker and the oxen in a farmer’s field in Shelby County where only the presence of corn remaining in the field beneath the snow kept the oxen and the man alive. When weather conditions improved, the farmer took one yoke of oxen as payment for the corn, and the worker returned with the other oxen to Mr. Waterman. The worker was then sent out a second time to purchase provisions for the winter.

Meanwhile the Waterman’s had taken in a Mrs. Black and her child from Cherokee County because her house had “burnt out” and they had no provisions to survive the winter. The scarcity of supplies and travel restrictions in the blizzard threatened the lives of all. At Peterson (Clay County), Father Bicknell took in another woman, an ill Lakota woman, traveling south with her community. After a month, historians report, the woman recovered and was asked to leave because of the shortage of provisions. Although “the snow was unusually deep that winter,” settlers believed, according to early historians, that this was “often done by the Indian women,” that is, native women often made such winter journeys alone and she could find her traveling companions. In the spring, her people returning north to Minnesota found her remains. “This enraged them,” historians report.

Historians suggest that this incident contributed to distrust and unrest arising from another incident near Smithland in which settlers disarmed Lakota hunters and killed many of the animals that they were keeping corralled on lands proximate to the town. Native hunters then fled without guns or game when a report circulated that General Harvey was approaching, although this did not prove to be true. Historians observe that the settlers knew the Lakota people would suffer (starve) in the winter without their guns or their game but had no way to return the guns. The angered Indian people confronted Waterman at his settlement but did no serious harm. In March of 1857 this group seems to have joined with others who violently attacked settlers near West Okoboji and Spirit Lake.

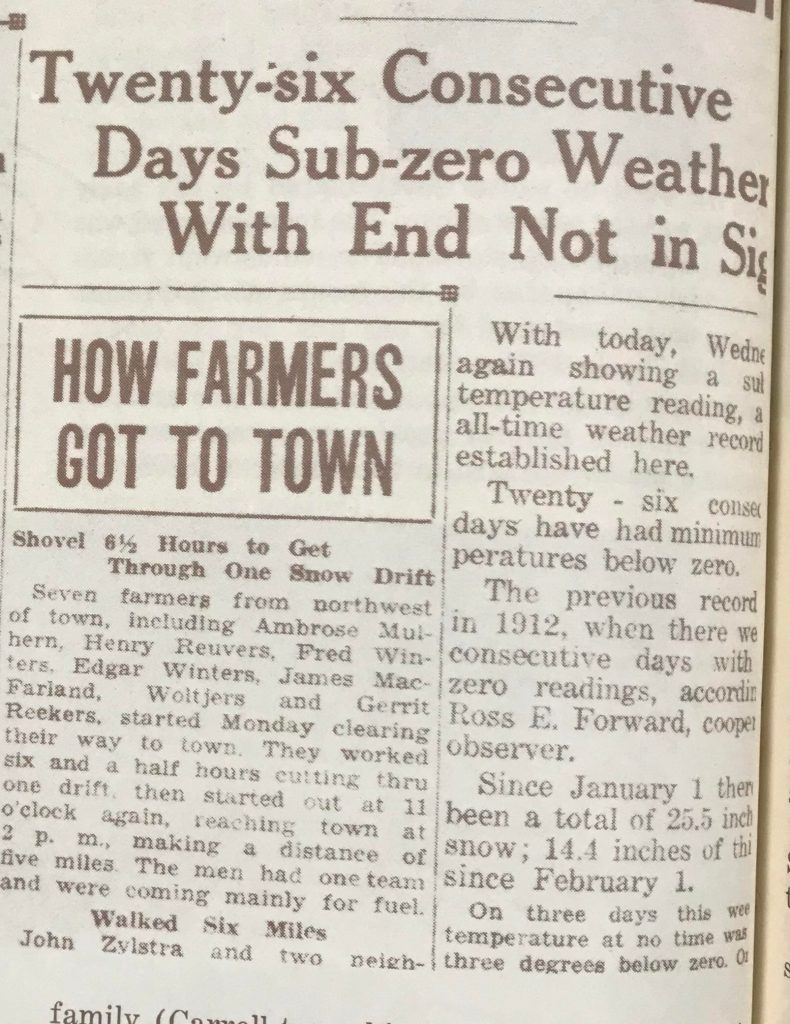

Though by 1885 there were 8,335 settlers in O’Brien County, when a blizzard was severe, they were still vulnerable to being lost and frozen to death, even yards from their back doors. The blizzard of 1888 was such an extreme event. The O’Brien County Bell of January 20, 1888 contained news of “sickening reports continu[ing] to come in concerning the recent great blizzard. There were six victims in this county.” A week later the Bell printed the numbers of victims in the region (Iowa, Nebraska, the Dakotas, and Minnesota): 190-205 dead.

In the winter of 1926-27, O’Brien was a settled county of some 15 thousand residents and not such a site of desperation, not for those who had established farms and towns there. Some farmers could turn their attention from survival to education. That winter, while the wind howled, the farmers completed their course of study in the first farmers’ night class and were photographed with their professor at their graduation.

Sources: D.A.W. Perkins, History of O’Brien County, Iowa, Sioux Falls, 1897; J.L.E. Peck, O.H. Montzheimer, and William J. Miller, Past and Present of O’Brien and Osceola Counties, Iowa, Indianapolis, 1914; O’Brien County Vertical File, SHSI; O’Brien County Bell, SHSI.