Hardship for Everyone in the Winter of 1842

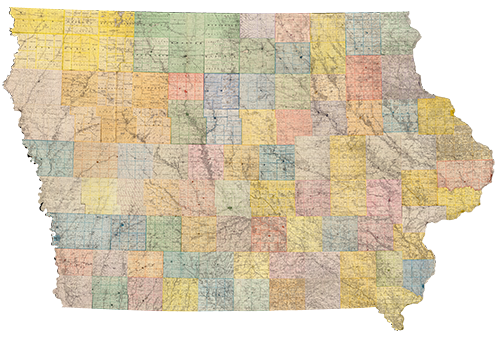

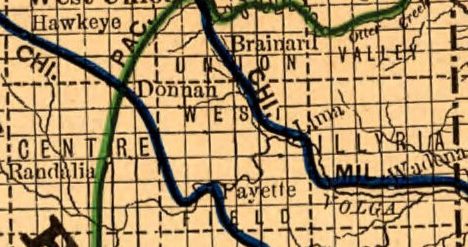

Fayette county, Iowa

By the winter of 1842, it had been nearly a decade since Black Hawk and his community of Sauk and “Fox” (Meskwaki) people had been forced from Illinois into Iowa and into even more competition with Dakota and Lakota peoples for hunting grounds (food sources) in what would become Iowa. The U.S. idea to establish a “neutral ground” between these two peoples and to encourage the “Winnebago” (Ho-chunk) people to establish residence in this in-between territory was in place when the winter of 1842 arrived.

Joseph Hewitt, a man familiar to early settlers, was said to have saved many native people from starvation that winter. While the severe winter and the unstable political and territorial arrangement prevented much successful hunting, Hewitt shared his resources.

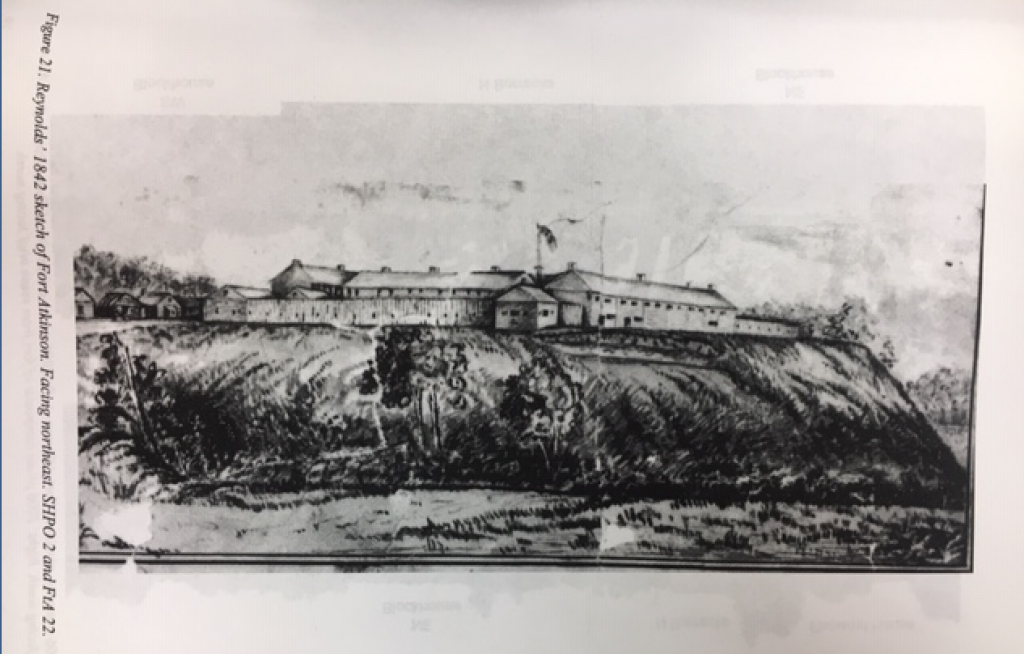

Thomas Peterman’s story provides more detail about the severity of that winter and the difficulty of maintaining a military operation in that territory. In the fall of 1842 a man began working for the government, conveying supplies to Fort Atkinson from Prairie du Chien in Wisconsin. In good weather, the trip took six days. But on October 20, 1842, fall was quickly turning into winter. On the twentieth it rained all day and the teamsters got soaked and cold before arriving at the fort. That night it snowed two feet. The Garrison was out of wood so all hands went to work to create a supply. As they worked, the snow on the ground increased to four feet. Then a message arrived from Captain Sumner that mail and supplies must be brought out from Prairie du Chien. But the snow was too deep for horses and mules so a team of oxen had to be sent and someone who could drive oxen. The same man who had recently arrived had such experience with oxen and so set out again. He describes the need to walk ahead on foot, tamping down the snow, to enable the team of oxen to continue along the path. Six miles per day was the best they could manage. When they stopped to make camp, they had to shovel snow before pitching their tents. Short of fuel and with provisions frozen solid, they chopped their food with an ax before eating. They finally reached McGregor, on the Mississippi River. In 1842, the town was only one lone log house lived in by the ferryman. There the travelers procured handsleds and crossed the frozen river to Prairie du Chien where they retrieved the mail and supplies.

Challenges did not end there. One member of the party, described as a malcontent, was found, on the return trip, to be smuggling whiskey—a lucrative and forbidden commodity to trade with native people. When discovered, the five-gallon keg was poured on the ground and the man prosecuted. While the whiskey only made a bad situation worse, the man’s discontent and illegal entrepeneurship might have been linked to the slowness of the government to pay these civilians for their work, especially under such conditions.

On the first of May 1843, snow was still on the ground.

In the winter of 1842-43, the settlement of African American (“Negroes”) in Westfield township had not yet been established. At the invitation of the Reverend George Watrous of the United Brethren Church, a few people relocated from Kankakee, Illinois, to Fayette County in 1852. Others from Kankakee followed, building a community with its own school, church, and cemetery, and its own cadre of men who enlisted to support the Union in the Civil War. Winters in northern Iowa continued to be repeatedly severe into the 1850s, but PWM does not yet have a story of these people’s experience of those winters in Fayette County. What we can say is that they were present and experienced such winters.

Sources: SHSI: Thomas Draper Peterman, Historical Sketches of Fayette County Iowa in the Forties and Fifties; Arlington History 1856-1983; Past and Present of Fayette County, Iowa, Indianapolis, 1910.