Fremont 1850s Blizzard

Fremont County, Iowa

Kat Perdock

In the dead of an 1850s winter, a man arrived in Tabor. He was traveling on foot, separated from his traveling companion, nearly frozen from the blizzard covering the Midwest in a blanket of snow. Though he stayed in Tabor for several weeks, his name is lost to history. He was far from the first to pass through in this way, and he wouldn’t be the last.

In the 1850s, the people of Tabor shared a silent understanding.

The town’s founder, George Gaston, had chosen to settle on the Loess Hills in the southwest corner of Iowa after the Missouri River flooded him and his people out of lower ground. He came to the valley to build a college, but as he acclimated to life on the border of a slave state, his priorities began to change.

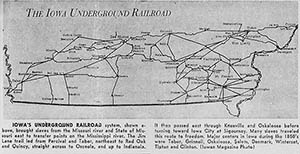

America’s Civil War would not begin until 1861, but abolitionists in free states were already taking subversive action. The Underground Railroad hit its peak during the 1850s, and Tabor’s location and relatively liberal population made it an ideal stop for slaves escaping from Missouri. Nothing about the Railroad was legal; the Fugitive Slave Act allowed for the capture and forced return of slaves in free states as well as slave states. Southern slave catchers haunted the border, popping into towns to hunt for fugitives, and the county’s own sheriff was legally obligated to do the same.

America’s Civil War would not begin until 1861, but abolitionists in free states were already taking subversive action. The Underground Railroad hit its peak during the 1850s, and Tabor’s location and relatively liberal population made it an ideal stop for slaves escaping from Missouri. Nothing about the Railroad was legal; the Fugitive Slave Act allowed for the capture and forced return of slaves in free states as well as slave states. Southern slave catchers haunted the border, popping into towns to hunt for fugitives, and the county’s own sheriff was legally obligated to do the same.

This just meant that the people of Tabor, like everyone helping at stations on the Railroad, had to work quickly and quietly.

Escaped slaves passed through Tabor alone and in groups. They could look forward to food and somewhere relatively secure to rest until the next leg of their journey; they rarely stayed for long, with the constant threat of detection on their minds and the minds of their benefactors.

The man fleeing slavery who arrived in Tabor during the blizzard stayed a few weeks. He was there long enough for residents to give him what medical aid they could and for them to learn where he’d come from – Linden, Missouri, close enough to be dealing with the same snow – and how he’d escaped.

He and his companion had been captured near the Iowa border and put in a log jail in Linden overnight, the floor held three feet off the ground on posts. The two men had first asked their jailor for some source of warmth in their cell. As their jailor put it when he spoke of them the next morning, “One of the slaves was havin’ a chill. It was so cold, wet and nasty, I wasn’t surprised.” He brought them a kettle of coals from the fireplace. As he was leaving, the men asked for something to drink, and the jailor gave them a pail of water. Had the men stayed where they were, they might have met the abolitionist search party coming to Linden for them. As it was, when the search party arrived, the men were already gone from their cell. While their captors were sleeping, they had dumped the coals from the kettle on the wood floor and allowed the fire to burn a hole through which they could escape.

The blizzard gave the men an opportunity, and their ingenuity in the situation saved their lives.

The Underground Railroad had no off season – in fact, people fleeing slavery often made a point of traveling in winter. Further east, the frozen Ohio River provided a famous path from slave state Kentucky to free state Ohio. People escaping slavery would have walked hundreds of miles between stations, in conditions much like the ones this particular Tabor visitor had weathered on his way there.

Though a blizzard could provide cover, it could be dangerous just the same. During the trek from Linden to Tabor, the blizzard worsened, and the two men who had escaped captivity in Linden were separated in the snow. The abolitionist search party looked for the missing escapee with no success. After a few weeks spent recuperating in Tabor, the man who did make it to Fremont County, Iowa, was able to continue his journey to safety across the Canadian border, undeterred by the snow lingering on the ground.