Early Flooding in Lee County

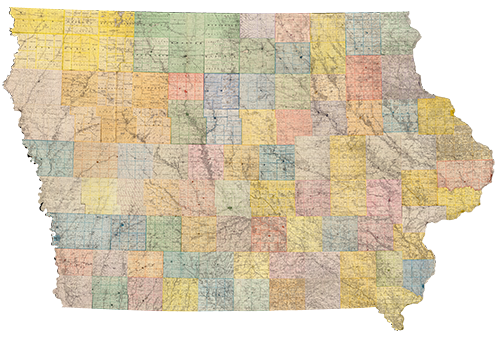

Lee county, Iowa

Amanda Lund

March 14, 1913

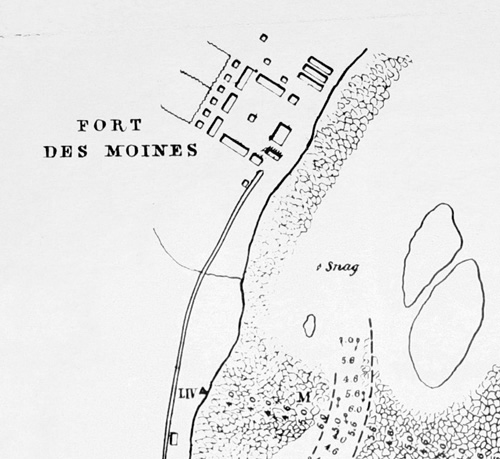

The possession rights of Native Americans of the “Forty-Mile Strip” expired June 1, 1833. This opened the land on the west bank of the Mississippi to white settlement from the Northern boundary of Missouri up to the northeast corner of Iowa. Tales of the beauty and fertility of the land attracted many. “So great was the desire of some men to secure claims in the new El Dorado that they did not wait for the expiration of the Indian limit of possession, but with more courage than discretion, more enterprise than respect for Indian treaty-right, or the good faith of the Government, intruded themselves on the domain in 1832.”

Mr. John Whitaker was one of the first noted men to cross into the territory in 1832, originally staking claim to land near the Skunk River. Though soldiers initially escorted him and his family to Schoc-ko-kon Island, they returned to the land near Skunk River shortly after and remained there through the expiration of the Native American possession rights. He claimed that upon his arrival there were three cabins near the Skunk River and only two near the ruins of Fort Madison.

By the summer of 1833, men and women continued arriving via the Mississippi River, making it a vital element of white settlement. The increased traffic on the Mississippi attracted more people to the river’s edge and within four years, Fort Madison was incorporated as an official town.

The severity of the winter 1833 caused one of the first recorded floods in Lee County history. Ice on the river formed to nearly thirty inches thick. When the mobile ice met with pieces of stationary ice, an ice gorge formed at the foot of the Des Moines Rapids by a town today called Montrose, Iowa. The gorge limited the water’s movement, causing a sudden rise that resulted in the first recorded water damage in the county.

Several steamboats were damaged in addition to the destruction of a few smaller craft as well as land and property.

“An elm tree three feet in diameter standing on the levee was cut more than half off by the floating ice, about 400 cords of wood were carried away, and a large quantity of pig lead piled up at the boat landing was buried under the mud and not recovered until the following June.”

Nearly a decade later, the ice formed again at the foot of the rapids creating an ice gorge over thirty feet high. River shipping was delayed for several weeks as the citizens waited for warmer weather to melt the ice. The rapids proved a relentless difficulty to anyone trying to navigate them. The varying depth and width of the river around the rapids created an unpredictability that left settlers seeking solutions.

In the late 1830’s, a dispute began over the territory surrounding the rapids between Iowa and Missouri. The resulting “bloodless Honey War” ended in 1849 with the Supreme Court supporting Iowa’s claim that the land north of the rapids—the site of modern day Keokuk– was theirs. Following the decision, Iowans planned to create a dam to regulate the rapids and ease river transportation. Plans for the dam were placed on hold until Keokuk and the Hamilton Water Power Company came together in 1899 to make it a reality. After several financial setbacks, work finally started on the dam in January of 1910.

The flood in the spring of 1913 brought an onslaught of ice that many speculated would overtake the dam that was still under construction. On the afternoon of March 24 people gathered on the riverbanks to watch as the ice broke over the rapids and piled up against the coffer-dam. The structure resisted the building pressure of the ice and water, and the coffer-dam was built higher to ensure the safety of the workers against the rising waters. By March 26 the ice jam broke downriver and the waters fell.

On April 7th a storm came in, threatening the same structure. In response, fifty men and truckloads of sand were brought in and piled onto the coffer-dam to help strengthen it against the wind and water. An additional one hundred men were brought in to continue reinforcing the structure while the rain poured. By May 1 the waters subsided once again and work was continued and was completed at the end of the month in 1913.