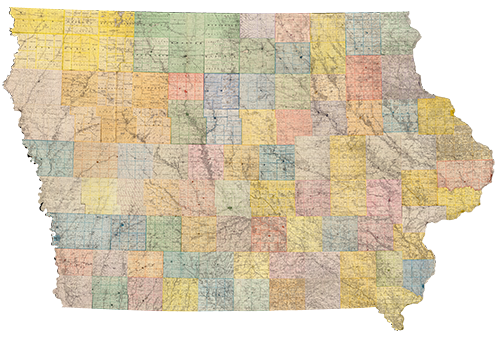

Crossing Boone Bridges

Boone County, Iowa

Emma Husar

6/6/1881

Through the whirl of wind and water, parted by the rushing steel,

Through the whirl of wind and water, parted by the rushing steel,

Flashed the white glare of the head-light, flew the swift-revolving wheel,

As the Midnight Train swept onward, bearing on its iron wings,

The evening, the darkness is dense and profound.

Through the whirl of wind and water, parted by the rushing steel,

Men linger at home by their bright, blazing fires:

The wind wildly howls with a horrible sound, and shrieks through the vibrating telegraph wires;

The fierce lightning flashes along the black sky;

The rain falls in torrents, the river rolls by….

This excerpt of a poem was published in The Holton Recorder (Kansas) in response to a flood in Boone, Iowa, on June 6, 1881. It is the story of “Brave Kate Shelley!” This was a moment in history that reached newspapers all over the country: San Francisco to New York. Kate Shelley, an Irish immigrant, was with her mother and siblings in their home in Boone beside Honey Creek and the Chicago and North-Western Railroad Bridge when a massive storm hit.

The Inter Ocean, a Chicago newspaper, published this excerpt of the poem in 1884 also commemorating the storm in Boone County three years prior. It captures well the helpless state of these Iowans amidst a summer tempest; however, it seems to understate the intensity of that river that surely “rolled by” with a life-taking force.

“Honey Creek, from Boone to Moingona, is a rapid and treacherous stream fed by many others of smaller size, all of which contribute to swell the usually unpretentious creek to the volume of a mighty river, the force of which was a severe test upon the strength of any structure opposing its course,” The Chicago Tribune notes. Along Honey Creek there are 21 bridges, 11 of which were destroyed in this flash flood. The train bridge over Honey Creek, right beside Shelley’s house, was among those destroyed. The rising water levels and “heavy and stiff winds” weakened the bridge until “The flood washed out the support trestles for the train bridge.”

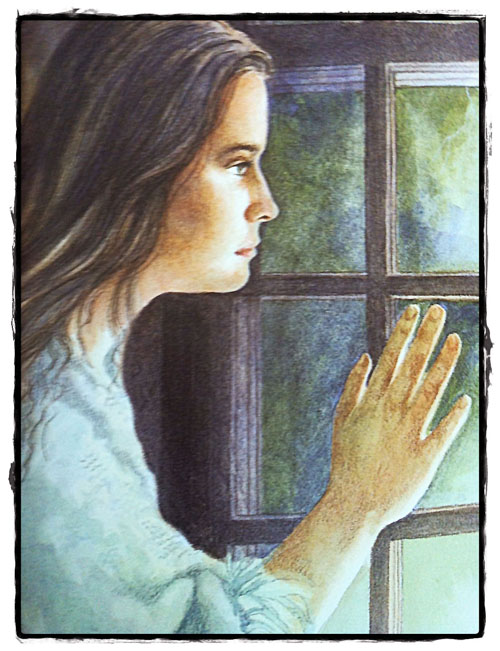

Held in her home by her mother’s will, Shelley listened to “the roar of thunder mingled with the sullen wash of the surging stream.” She kept a keen gaze on the world outside that house—even though she was encouraged to stay, she had an itch to warn the men at “Moingona, a station about a mile from Honey Creek” that the bridge appeared far too dangerous to cross. After suddenly witnessing the fall of the train Ed Wood was on, she leaped up and rushed out to warn Moingona, for, she knew that another train was bound to cross at midnight, and that one carried 200 passengers.

Held in her home by her mother’s will, Shelley listened to “the roar of thunder mingled with the sullen wash of the surging stream.” She kept a keen gaze on the world outside that house—even though she was encouraged to stay, she had an itch to warn the men at “Moingona, a station about a mile from Honey Creek” that the bridge appeared far too dangerous to cross. After suddenly witnessing the fall of the train Ed Wood was on, she leaped up and rushed out to warn Moingona, for, she knew that another train was bound to cross at midnight, and that one carried 200 passengers.

…in the Valley yonder lies

Death’s debris in weird confusion, altar fit for Sacrifice!

Dark and grim the shadows settle where the hidden perils wait,

Swift the train, with dear lives laden, rushes to its deadly fate!

Ed Wood was one of two survivors of the initial train crash that was the final test for the Honey Creek Bridge. Wood says, “I [heard] the timbers begin to crack….The weak place proved to be in the center of the bridge, directly over the main current, which we had not yet reached. To this point the engine leaped in a second, and down we went with an awful crash into twenty-five feet of surging water.” Once he hit the water and lost sight of his workfellows, he flung about, lungs filling with water as he surged with the river, 3 feet underwater. Wood’s struggles to survive the deadly current were not in vain: he struck driftwood where the water was around twelve feet deep. He drifted along until, as he recalls,

“The water went down very fast, and in about half an hour was not more than up to my waist, but was still very deep between me and either shore. Next I noticed the waves rolling down towards me four or five feet high and I felt sure that the Boone reservoir had bursted, and that it was all over with me then. The sight was grand and terrible, but it was all over in a moment. The waves swept over me, and the waters again went down quickly, leaving me clinging to the branches of a willow tree. [What he saw next was] the light of Kate Shelley’s lantern gleaming out in the dark woods.”

Kate Shelley also rushed. She marched right into a storm where, The Inter Ocean recalls, “So great was the velocity of the wind that many buildings were destroyed.” She was determined to make it to the station so those passengers would escape their “deadly fate.” However, in order to do so, she had to cross “the high trestle bridge over the Des Moines River.” Below that bridge, in only an hour, the water level had risen six feet, and counting. Fearless, she mounted the structure and crawled all the way across: “The darkness was intense, except with the dazzling lightning revealed the timbers and the surging and seething waters below.” Although she nearly fell off of the bridge due to the thrashing wind and rain, in the end, not only did she bring Wood and the other and only survivor of the first crash to safety, but she managed to cross the bridge so they could stop the next train in the nick of time.

Kate Shelley also rushed. She marched right into a storm where, The Inter Ocean recalls, “So great was the velocity of the wind that many buildings were destroyed.” She was determined to make it to the station so those passengers would escape their “deadly fate.” However, in order to do so, she had to cross “the high trestle bridge over the Des Moines River.” Below that bridge, in only an hour, the water level had risen six feet, and counting. Fearless, she mounted the structure and crawled all the way across: “The darkness was intense, except with the dazzling lightning revealed the timbers and the surging and seething waters below.” Although she nearly fell off of the bridge due to the thrashing wind and rain, in the end, not only did she bring Wood and the other and only survivor of the first crash to safety, but she managed to cross the bridge so they could stop the next train in the nick of time.

As the poem goes on to state:

“[Kate Shelley] saved the lives of sleeping travelers swiftly to death’s journey borne…

Saved! Ere yet they know their perils, come a warning to alarm;

Saved! The precious train is rising on the brink of deadly harm.”